This post is intended to provide (rather too much) detail into my thinking as I attempt to synthesize several conflicting data sources into a ‘best guess’ drawing of an indefinite border between two townships in the Catskill Mountains of New York.

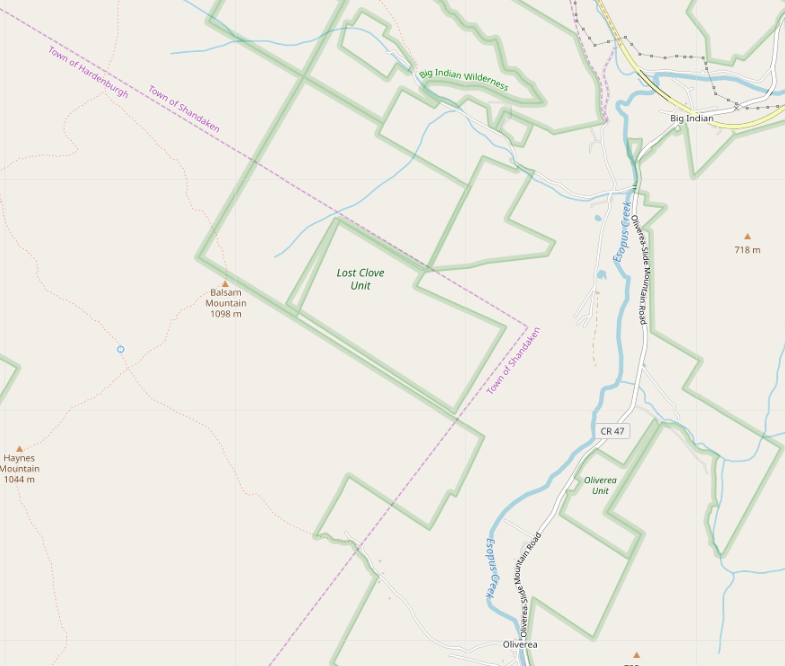

Our story begins when I noticed, while doing an import, that the Lost Clove Unit of New York City’s watershed recreation lands was badly misaligned with neighbouring parcels of state wilderness area, and that nothing seemed to join at right angles.

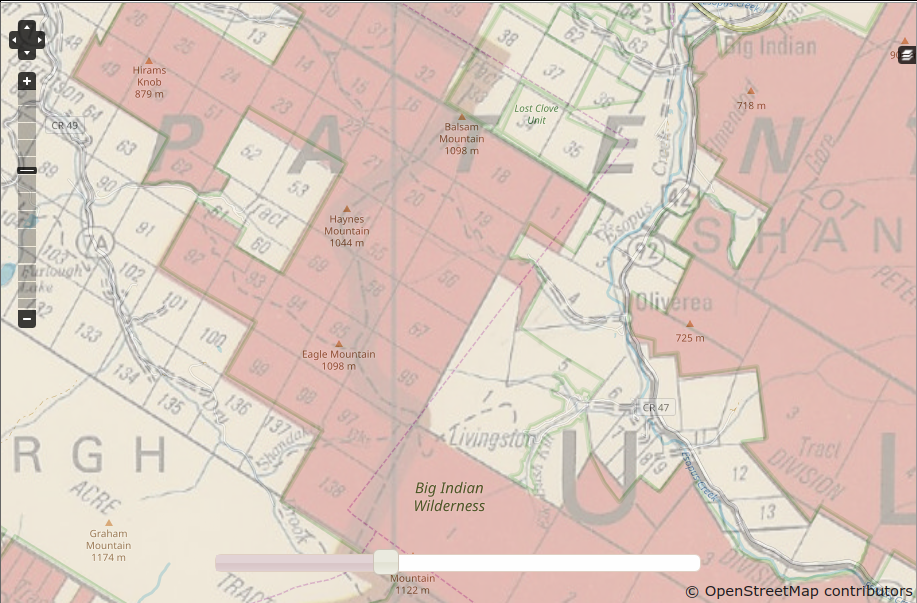

In doing this sort of cadastral research in the Catskills, I’ve found that a great many parcels to this day follow the lines of the Dutch and English land grants of the 17th and 18th Centuries. This practice is so common, in fact, that the managers of New York’s Catskill Park commissioned a 1970 map showing state-owned lands (as they stood at the time; the state has acquired additional parcels in the intervening years) referenced to the land grant, great lot and small lot. (Warning: This map is imperfectly rectified, so it’s unwise to trace from it. It’s still usefui as a general guide to how things are laid out.

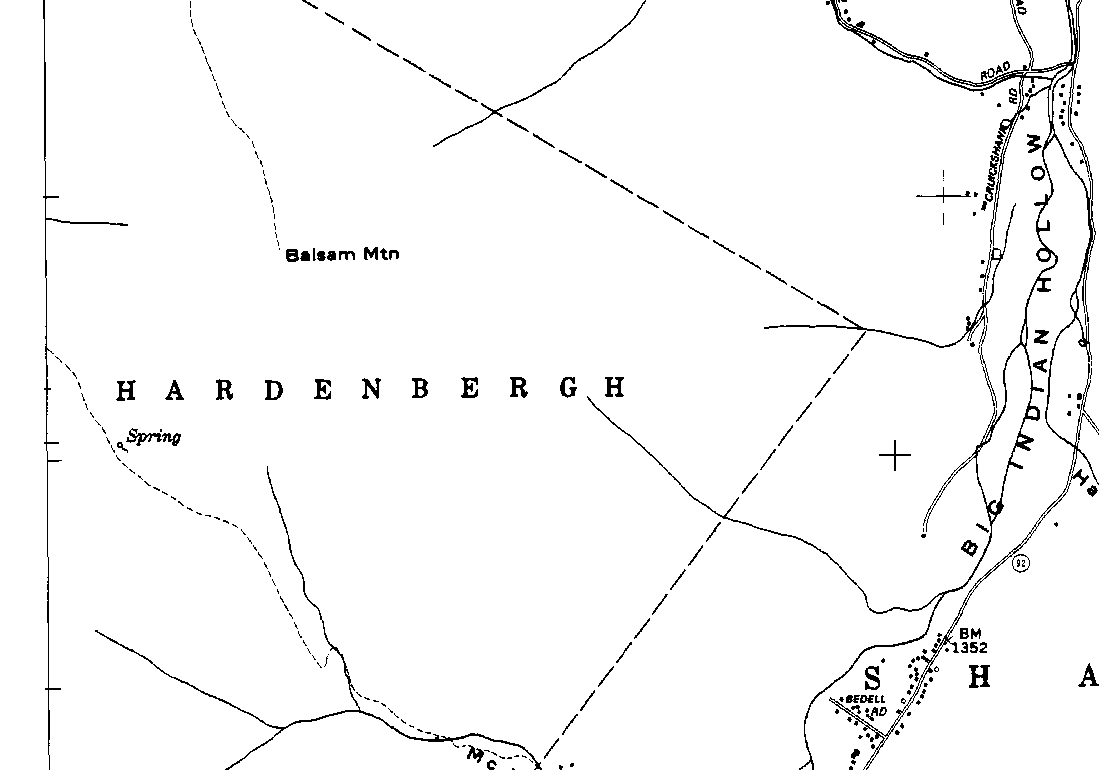

In comparing OSM against the map of the land grants, I see that the vast majority of the property lines do, in fact, follow the old land subdivisions. But what leapt to my eyes was a surprise: the line between the Towns of Hardenbergh and Shandaken on the state map is significantly different from the one in OSM. The map from the state shows the boundary following the ridge of Balsam, Haynes and Eagle Mountains. The one in OSM is a zigzag of straight lines between the ridge and the Esopus Creek, , as far as a mile off at one corner. Something’s strange here!

OK, that state map is pretty old, but I’m pretty sure that everything outside the wilderness areas east of the ridge is Shandaken Township. What does New York State’s official shapefile (which is actively maintained) say? Fire up OSM, and set up the map and image layers, and let’s see. Looks as if the line is still up there on the mountain tops!

Throwing in the Ulster County tax parcel data as another layer shows that the county has roughly the same idea as the state. The two stray apart by as much as a couple of hundred feet, but that’s actually not all that bad for an indefinite boundary in deep woods and broken terrain. I’ll say that’s good enough.

Particularly since they both align with the 1970 state map - Note that the tax parcels are also in decent agreement with the lots in the old land grants - at least good enough to identify the lot numbers.

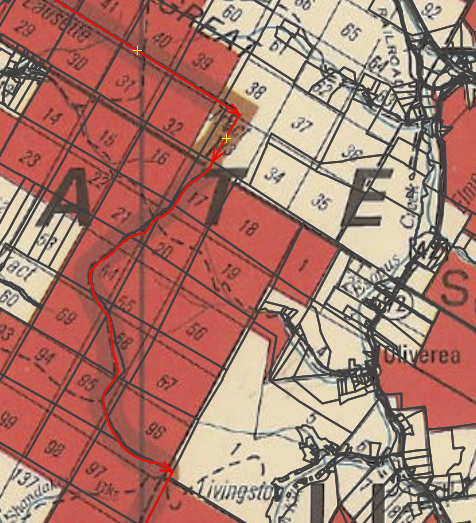

And, whoops, it looks as if there’s some misalignment farther south as well. The county and state agree perfectly, but OSM appears to be astray.

For what it’s worth, the 1970 map also has pretty fair agreement here.

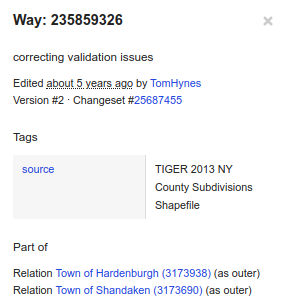

OK, before I start charging off to fix this, where did the OSM data come from? Select the way that corresponds to the Hardenbergh-Shandaken town line, and look up its metadata:

TIGER 2013. We know that TIGER 2010 had a problem with political boundaries in New York, but 2013 got a fresh copy from USGS, so it looks as if USGS has the problem, also. Let’s take a troll through the historical topo maps and see if we can spot what’s going on.

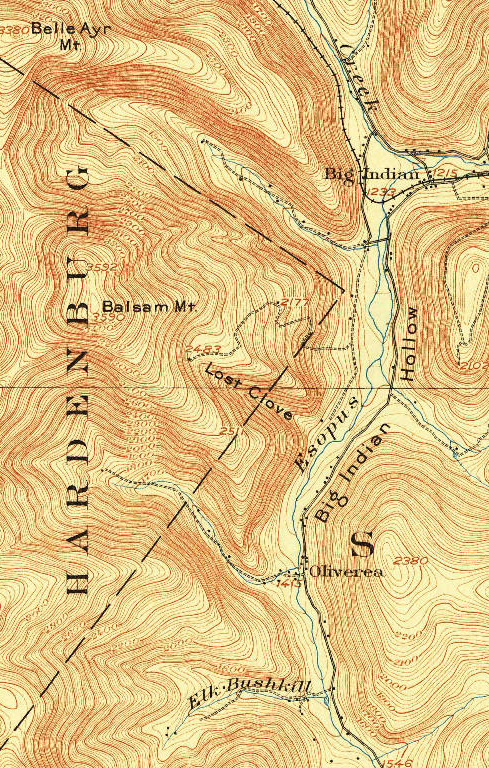

There is essentially only one 15-minute topo (the Phoenicia quadrangle) from the area, based on the 1903 survey. Sure enough, it shows the questionable boundary. For all I know, that’s where the line was in 1903! Printings of this quadrangle from as late as 1948 show the line in the same place.

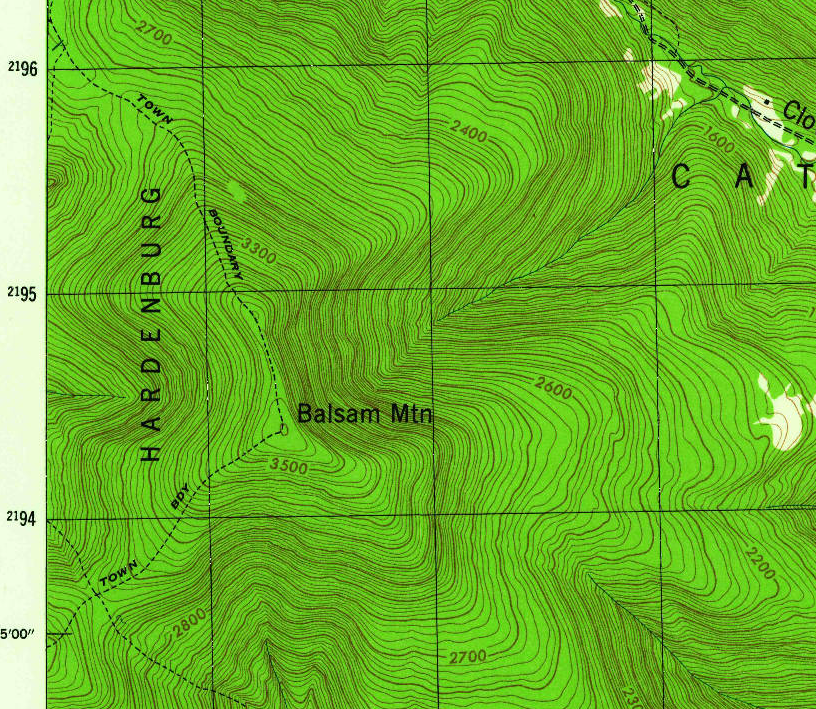

In 1945, the Army Map Service produced the first 7.5-minute quadrangle map of the affected area (Shandaken). It moves the town boundary up to the ridge, while continuing to misspell ‘Hardenbergh’.

The 1960 USGS 7.5-minute quadrangle revises the town boundary to something close to what the state has currently, while retaining mapping for the hiking trail that follows the ridge. It also finally spells ‘Hardenbergh’ correctly.

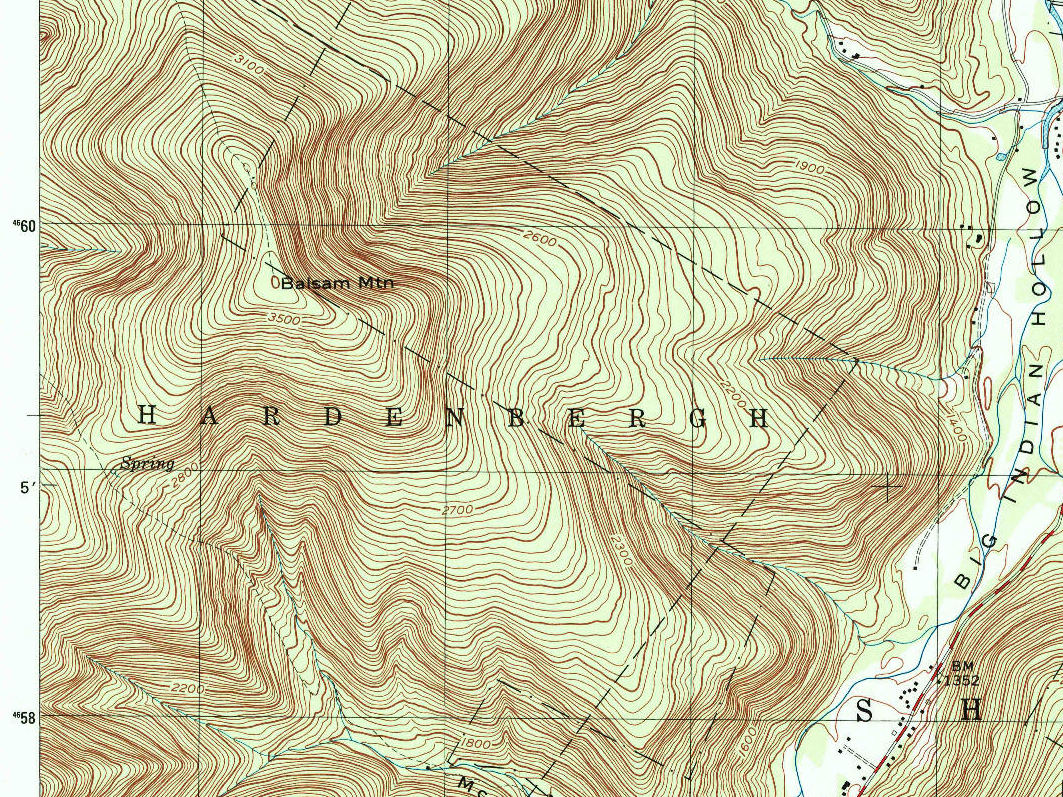

But in the 1997 edition, the geometry from 1903 is back - this time at 7.5-minute scale. ‘Hardenbergh’ is still spelt correctly, but the zigzag of straight lines matches the 1903 survey, discarding the changes from 1945 and 1960.

It appears that the data source for this reversion was likely the 1973 NYS Department of Transportaion 7.5 minute topo map, whose black overprint layer lacks the boundary corrections of the 1946 and 1960 maps, although it does spell ‘Hardenbergh’ correctly.

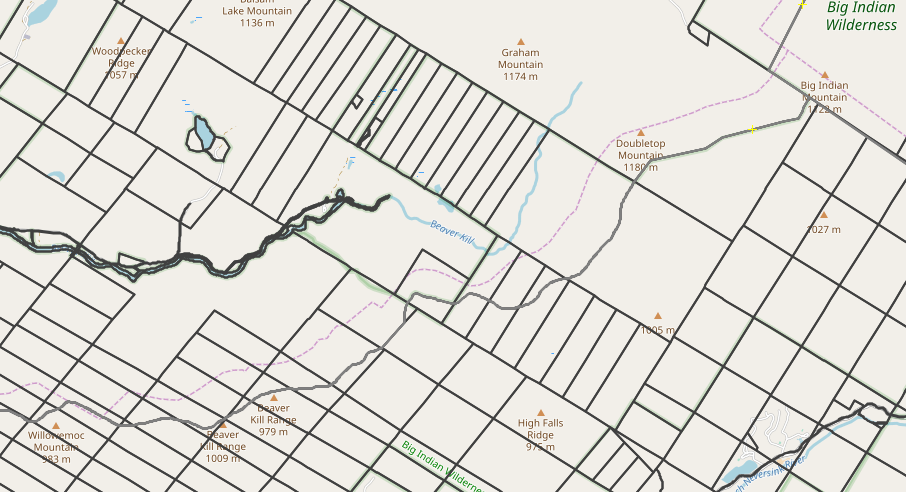

So where do we go from here? Since three separate agencies today (NYS Department of Homeland Security, NYS Department of Environmental Conservation, Ulster County) all agree on the boundary now, and since they are the ones with the greatest interest in getting it right (they collect the property tax on the land!), I’m going to go with their location of the line.

To deal with the small differences and make everything topologically consistent, I’ll use county parcel data for the town line between Big Indian Mountain and the corner north of Balsam Mountain, and conform the boundaries of the Big Indian Wilderness and the Lost Clove unit to the county data in that region for topologic consistency. Elsewhere, I’ll use state data for the town lines except for this area (conflating points at the junctions, and revise the lines that separate the Towns of Hardenbergh, Shandaken, Denning, Neversink and Wawarsing, all of which are misaligned badly to state and county cadastre.

The results will surely not be 100% correct, since surveys disagree, but will at least be topologically consistent and better than what’s there.

Sometimes, mapping is like writing Roots!

P.S.: It’s somehow appropriate that Hardenbergh should be the township with the trouble.

http://clermontstatehistoricsite.blogspot.com/2009/10/great-hardenbergh-patent.html http://clermontstatehistoricsite.blogspot.com/2009/12/hardenbergh-2-even-harder.html

give some idea about the complexity of local history. The feudal land tenure in the area even gave rise to a civil war.

Discussion

Comment from mikelmaron on 6 December 2019 at 17:00

Fascinating post @ke9tv. This is one reason I love OSM .. as you try to map the world today, you engage in an ongoing centuries, or longer old, conversation about what’s happening in our world.